The Evolution of the

Central Axis

The planning, construction, and refinement of Beijing Central Axis encapsulate the ideals of the Chinese civilization in pursuing a perfect order in managing a nation, a city, and even daily life, leading to rigorous traditions and order in urban construction. Beijing Central Axis was closely connected with the construction of Dadu of the Yuan Dynasty from its inception. As the heart of the capital city of the Yuan, Ming, and Qing dynasties and modern China, Beijing Central Axis is directly associated with a series of events with global impacts, bearing witness to historical transformations of Chinese society from a traditional dynastic system to a modern state. It was also directly associated with the abdication of the last Qing emperor, the termination of the dynastic system, and the founding of the People’s Republic of China.

Beijing Central Axis is the accumulation of more than seven centuries of urban remains from the Yuan, Ming, and Qing dynasties as well as newer development in modern times. It witnesses the development of the Chinese civilization and the enduring impact of the traditional Chinese philosophy of capital central axis planning. Having gone through five phases of development, Beijing Central Axis was initially constructed during the Yuan Dynasty, fully formed, and evolved during the Ming and Qing dynasties. It was further developed and preserved in modern times, forming the present-day urban complexes with their majestic presence and strict orders. There are historical remains from these five phases of development that have survived to the present day and are combined to form the historical layers of the nominated property.

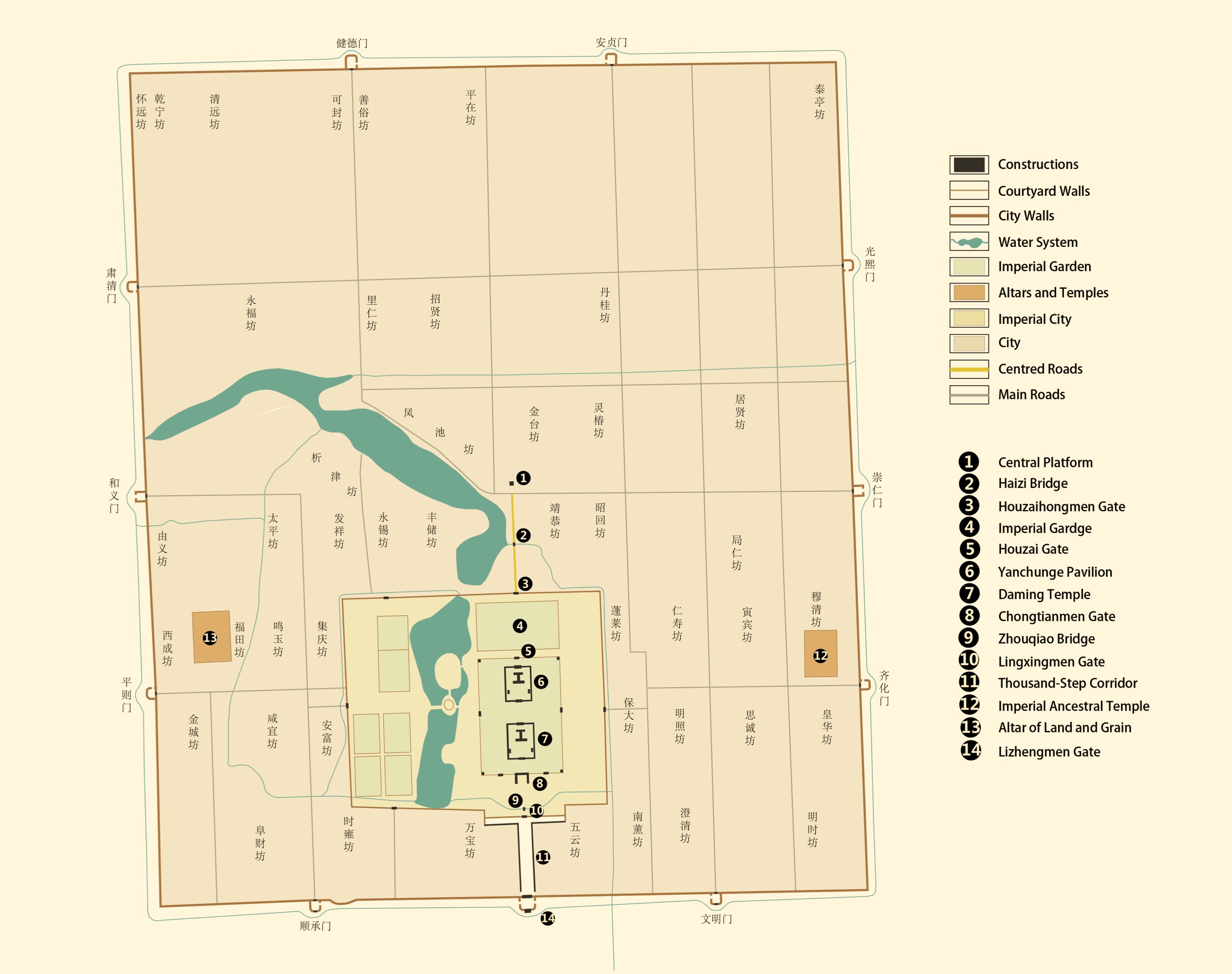

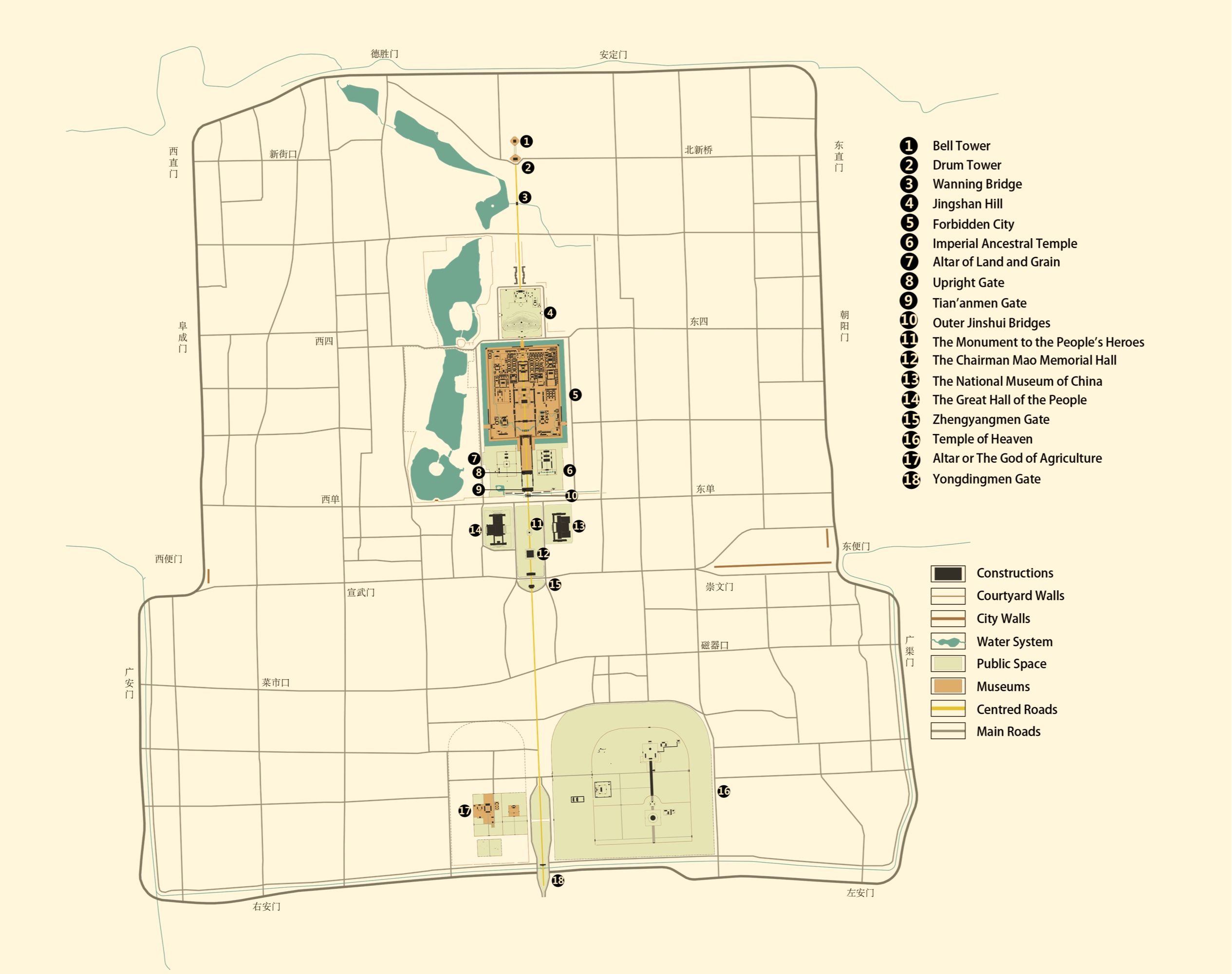

Historical map showing the Dadu of Yuan

Source: THAD team for preparing the nomination dossier of Beijing Central Axis

Reference: Hou Renzhi, Beijing Historical Map Atlas (administrative district series) [M], Wenjin Publishing House, 2013

The location and basic form of Beijing Central Axis were established during the construction of Dadu. The layout of the northern section has been kept intact. The Wanning Bridge has remained in the same location since its construction during the Yuan Dynasty. These significant remains from the early stage of development serve as the physical evidence for the continuation of the central axis of Dadu of the Yuan Dynasty into the Ming and Qing dynasties and modern times.

Beijing Central Axis started to take shape in 1267 when the construction of Dadu was launched. The datum point of Dadu was selected on the east bank of the Jishuitan Lake (presented-day Shichahai Lake’), where the Central Platform and the Central Tower were built. From this point to the south, the city’s central axis was formed, along which the palace city was built, and the city’s boundary in all four directions was demarcated with the Central Platform as the center. The locations of temples, altars, and government offices were then determined, and the Imperial Ancestral Temple and the Altar of Land and Grain were built on the east and west sides of the central axis of Dadu, based on the principles from the Kao Gong Ji. By the time the lifang neighborhood system was put in place, the checkerboard pattern of streets and alleys across the city was formed. Dadu was constructed according to the capital planning paradigm prescribed in the Kao Gong Ji.

The central axis of Dadu started from the Central Platform and went southward through the Wanning Bridge and the Houzai-hongmen Gate (the north gate of the imperial city). Within the palace city, the axis passed through the Yanchun Hall and the Daming Hall, where the emperor resided and managed state affairs. Across the Chongtianmen Gate (the south gate of the palace city), the axis went through the Zhouqiao Bridge. It exited the imperial city at the Lingxingmen Gate (the south gate of the imperial city). The axis terminated at the Lizhengmen Gate (the south gate of the outer city) after passing through the T-shaped imperial square, totaling 3.75 kilometers.

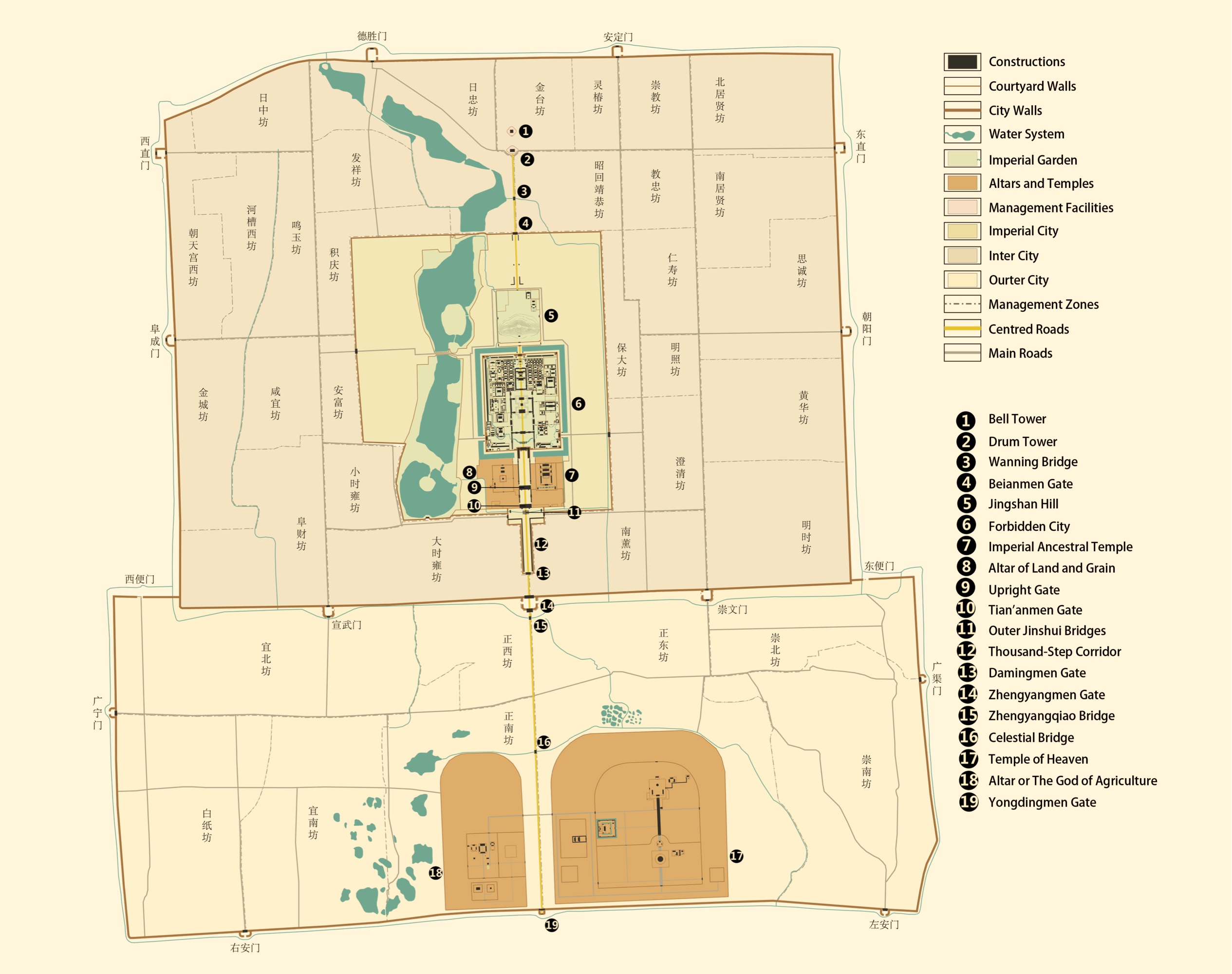

Map of Beijing in the Ming dynasty

Source: Drawn by the THAD team for preparing the nomination dossier of Beijing Central Axis and transferred by Tencent

Source: Transferred by Tencent, referring to Hou Renzhi, Beijing Historical Map Atlas (administrative districts, series M1), Beijing Publishing Group, Wenjin Publishing House, 2013.

From the construction of the Beijing City of the Ming Dynasty to the completion of the wengcheng barbicans of the outer city, the construction of the inner and outer cities of Beijing gave rise to a “凸” shape walled-city framework. During this period, Beijing Central Axis was formed with a total length of 7.8 kilometers. The overall layout of Beijing Central Axis consists of the location and orientation of the central axis roads, and the layout of nominated components bears witness to its formation during this period. In the urban expansion, Beijing Central Axis has always determined the urban form and pattern. Existing ancient imperial palaces and gardens, sacrificial buildings, and city management facilities were all established during this period, marking the formation of the basic functional layout of the Axis.

The development of Beijing Central Axis during this period could be further divided into two phases, the construction of the inner city and the outer city. The construction of most buildings along Beijing Central Axis, as seen today, was completed during the construction of the inner city. The construction of the outer city took Beijing Central Axis as the governing principle by placing the Yongdingmen Gate, the central south gate of the outer city on the Axis, thus extending the full stretch of Beijing Central Axis to its present layout totaling 7.8 kilometers.

The construction of the central axis of the inner city of Beijing based on the central axis of Dadu of the Yuan Dynasty started in 1406, marked by the construction of the palace city. Ordered by the emperor, the palaces, temples, altars, and gates should be built following the Nanjing model but larger and more magnificent. Between 1415 and 1419, new inner city walls were completed, which was nearly one kilometer south of the southern walls of Dadu of the Yuan Dynasty. In 1420, many important components of the axis were completed. These include: the Bell and Drum Towers in the north; the palace city (present-day Forbidden City) at the center with the Wansui Hill to the north as the imperial garden (present-day Jingshan Hill); the Imperial Ancestral Temple and the Altar of Land and Grain symmetrical on the east and west, and the Altar of Heaven and Earth(present-day Temple of Heaven) and the Altar of Mountains and Rivers (present-day Altar of the God of Agriculture) symmetrically aligned on the east and west of the central axis at the south end. The unpaved southern section road also preliminarily took shape. In this year, the Ming Dynasty officially moved its capital to Beijing.’ In 1439, the Zhengyangmen Gate Tower and Archery Tower on the south of the inner city were built, marking the completion of the construction of the inner city of Beijing in the Ming Dynasty and the establishment of most heritage components that have survived to this day, including imperial palaces and gardens, sacrificial buildings, and city management facilities. At this stage, Beijing Central Axis started from the Bell and Drum Towers at the northernmost end, extended through the Wanning Bridge, the Wansui Hill, the Forbidden City, the Upright Gate, the Chengtianmen Gate (present-day Tian’anmen Gate), the T-shaped imperial square and ended at the Zhengyangmen Gate. The total length was 4.75 kilometers.

The construction of the outer city of Beijing was undertaken to improve the military defense system of the capital in 1553. A “凸” shape walled-city framework was formed by including the Altar of the God of Agriculture and the Temple of Heaven in the outer city. The total length of the outer city walls was 28 li (around 14 kilometers). The middle road along the south section of the central axis was extended to the Yongdingmen Gate, the central south gate of the outer city. Except for the middle roads on the central axis, which were straight and wide, all other streets and alleys were winding and narrow. This presented a striking contrast between the pattern of streets and alleys and cityscapes around the southern section of the central axis and those in the northern section. The wengcheng barbicans of the outer city were built in 1564 to further enhance the defense of the city gates, which marked the completion of the construction of the outer city. The completion of the outer city also symbolized the extension of Beijing Central Axis to its full length of 7.8 kilometers.

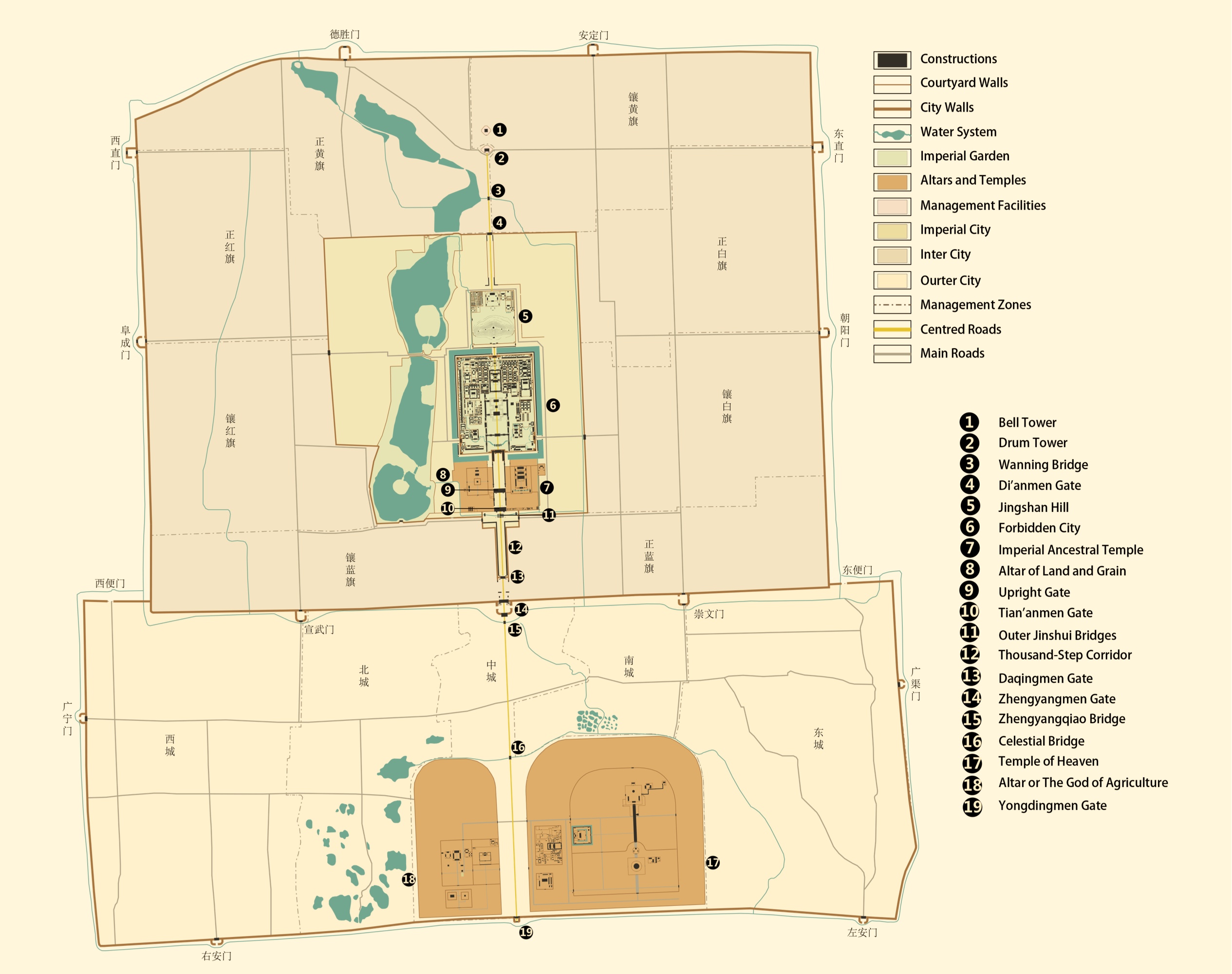

A historical map from the 15th year of the Qianlong reign

Source: Drawn by the THAD team for preparing the nomination dossier of Beijing Central Axis and transferred by Tencent

Source: Transferred by Tencent, referring to Hou Renzhi, Beijing Historical Map Atlas (administrative districts, series M1), Beijing Publishing Group, Wenjin Publishing House, 2013.

During the partial addition and reconstruction of the building complex in the second half of the Ming Dynasty to the end of the Qing Dynasty, the layout of Beijing Central Axis was maintained and carried forward with partial additions and renovations in the latter half of the Ming Dynasty and throughout the Qing Dynasty. In particular, the layout adjustments and improvements of the Jingshan Hill and the Temple of Heaven during the Qianlong reign (1736-1795) further enriched and enhanced the orderly landscape of the Axis that has survived to the present day.

Beijing remained the capital of the Qing Dynasty after 1644. In 1749, the Hall of Imperial Longevity was expanded and relocated from the northeast of the Jingshan Hill to the north on the Axis to enhance its superior importance as the place for worshiping the late emperors and empresses of the Qing Dynasty. The renovations and additions to the Jingshan Hill not only enriched the hierarchical order of the central axis landscape but also gave more prominence to the centered and east-west symmetrical layout. The road on the south section of Beijing Central Axis also underwent renovations from 1689 to 1729, where the imperial road exclusively used by the emperor was paved with bricks and stone to mark the ritual route the emperor took from the Forbidden City to the south during sacrificial events and other outings. This section of the Beijing Central Axis is of the same length: 7.8 km (4.85 mi.).

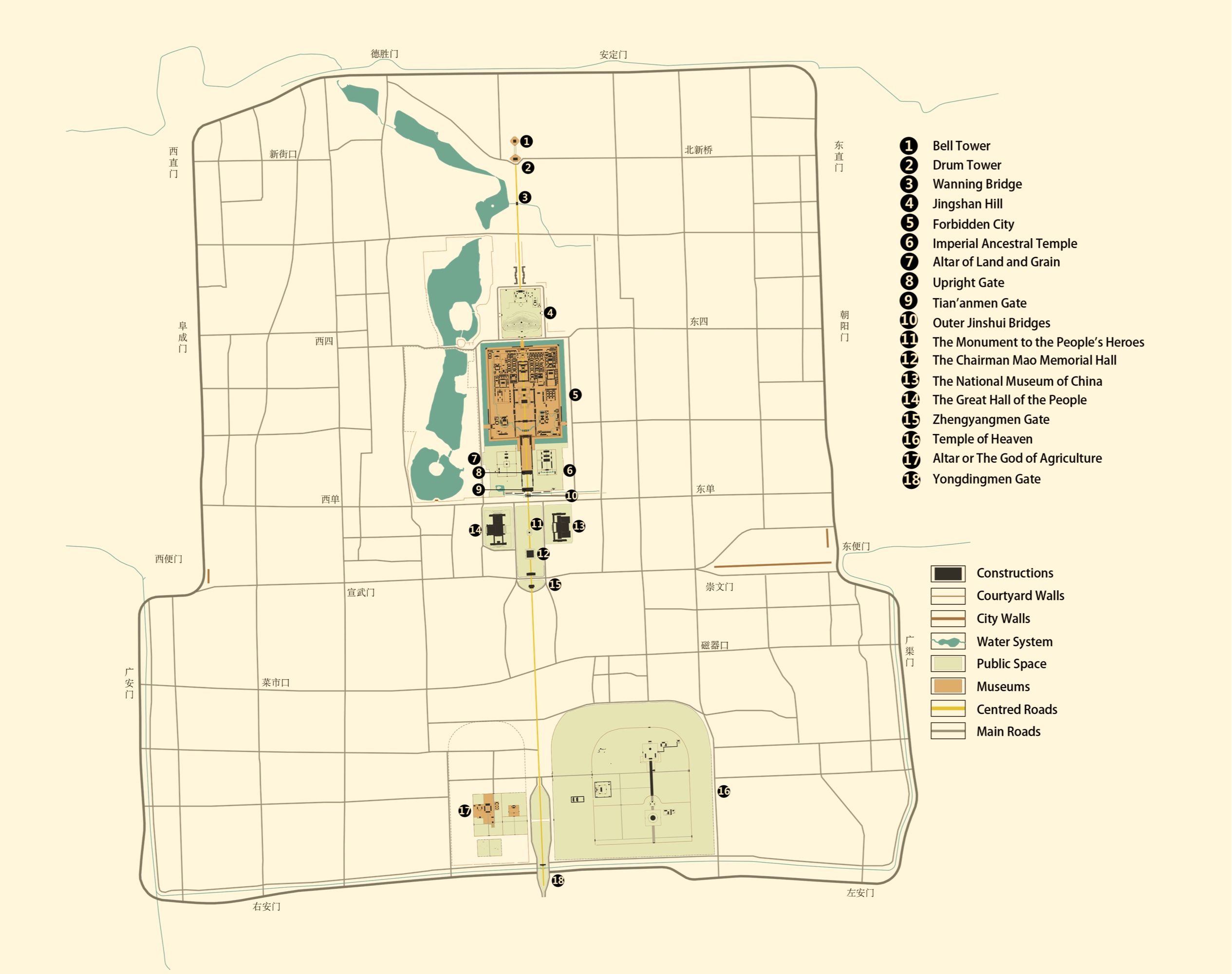

A satellite image showing the current state

Source: Beijing Institute of Surveying and Mapping

From the abdication of the last Qing emperor in 1912 to the expansion of Tian’anmen Square in 1977, the symmetrical layout with Beijing Central Axis was further continued and reinforced by the planning and construction of Tian’anmen Square, which reflected people’s need for spacious open public spaces. The transformation toward public access to the ancient imperial palaces and gardens, sacrificial buildings, city management facilities, the correspondent renovations of the layout and landscape, and the phased establishment of the layout, architecture and landscape of the Tian’anmen Square Complex were unique achievements during this phase of development.

The promulgation of the Imperial Edict of the Abdication of the Qing Emperor by the Qing government in 1912 terminated the dynastic system that had ruled China for more than 2,000 years. The political and sacrificial activities in the imperial buildings were gradually brought to an end. It was against the backdrop of the modernization of the old city of Beijing that the public access transformation of Beijing Central Axis unfolded. The Capital Municipal Office’ first started to renovate the once-closed imperial buildings along Beijing Central Axis in 1914. The imperial compounds along Beijing Central Axis and on both sides underwent a series of functional adjustments, with the palaces, gardens, temples, altars, and squares opened to the public and used as museums and civil parks. In the same year, the Altar of Land and Grain was turned into the Central Park, the first public park in Beijing’s old city. Garden facilities and landscapes were also added to meet the needs of park visitors. After that, the Altar of the God of Agriculture (1915), the Temple of Heaven (1918), the Forbidden City (1925), the Jingshan Hill (1928), and the Imperial Ancestral Temple (1930) were opened to the public successively. From 1913 to 1915, the closed imperial square in front of the Tian’anmen Gate was transformed into a public space for leisure activities with trees planted all over the square, turning Tian’anmen Square into one of the few open and spacious public spaces in the old city.

On October ls,1949, the founding ceremony of the People’s Republic of China was held at the Tian’anmen Gate and Square. The Monument to the People’s Heroes was erected on Beijing Central Axis at the center of the square from 1952 to 1958, which, as the first monumental construction located at Tian’anmen Square since the foundation of the PRC, highlighted the central location. Two large-scale expansions were done to Tian’anmen Square in the 1950s and 1970s to form the layout that exists today. During the first expansion of Tian’anmen Square from 1958 to 1959, the National Museum of China and the Great Hall of the People were built on the east and west sides of the square respectively. The second expansion started with the construction of the Chairman Mao Memorial Hall in the south central location of the square in 1976 when the southern boundary was extended to the Zhengyangmen Gate Tower. The construction was completed in 1977, and the square’s symmetrical layout, along the spine of Beijing Central Axis, was formed. After going through the process of public access transformation, a new urban center has emerged on Beijing Central Axis with Tian’anmen Square at its core, which is based on the layout from the Yuan, Ming, and Qing dynasties. Today, the urban axis totals 7.8 kilometers from the Bell and Drum Towers in the north to the Yongdingmen Gate in the south.

Beijing Central Axis still plays a leading and guiding role as the baseline of urban development and is therefore preserved and respected in all versions of urban master plans. Continuous heritage conservation, archeological studies, remediation, and restoration of the historic environment are also in place for Beijing Central Axis as an integrated cultural heritage property to guarantee the continuity and transmission of the value of the nominated property.

After 1978, with the increasing awareness of urban heritage conservation among people from all walks of life, the cultural features and heritage value of Beijing Central Axis gained more attention, and cultural heritage conservation and historic environment remediation were methodically carried out. Meanwhile, Beijing Central Axis remained the basis for urban development in Beijing, leading the evolution of the spatial framework of Beijing in various versions of the city’s master plans. Nominated components of Beijing Central Axis have all been registered as protected sites or listed buildings of various levels for which a large number of conservation projects have been carried out.

In the 1990s, repair projects for the Drum Tower, the Wanning Bridge, some protected buildings in the Altar of the God of Agriculture, and the Upright Gate were completed successively, after which the Upright Gate, the Zhengyangmen Gate, and the Altar of the God of Agriculture were also opened to the public. Archeological research and conservation work have not ceased since the start of the 21st century. Repair work has been done to the Bell and Drum Towers, the Imperial Ancestral Temple, the Jingshan Hill, and the Forbidden City, and areas allowing public access in the Forbidden City, the Jingshan Hill and the Imperial Ancestral Temple have gradually increased. The Southern Section Road is currently undergoing archeological excavation and research. As for the historic environment of Beijing Central Axis, the integrity of the orderly landscape of Beijing Central Axis was gradually restored through the study of historical documents and archeological research by combining multiple means of architectural reconstruction and presentation, historic fabric renewal, and urban regeneration.

Beijing Central Axis continues to play a guiding role as the basis of Beijing’s urban development, as it has done across history. The Beijing Master Plan (2016-2035) underlines the major role of the “traditional central axis” (Beijing Central Axis) in shaping the historic layout of the ancient capital of Beijing. The plan specifies that “the future development of the traditional central axis and its extensions should focus on its cultural function and lay emphasis on enhancing the spatial order of the traditional central axis, so that the traditional central axis and its extensions can continue to dominate the development of the urban spatial framework of Beijing.