Ancient Central Axis

From the perspective of materialist history, the emergence and development of the central axis of the ancient Chinese capital underwent a long process, and its planning pattern was the product of the development of the capital’s functional and morphological complexity to a certain stage. The Qin Dynasty (221-207 BCE) was a united empire, but its capital did not yet have a layout with a single palace city.

Similarly, the layout of a single capital axis running through the entire city did not take shape until the construction of Yebei City during the Cao Wei Period (220-226 CE), and one was officially established in Luoyang City of the Northern Wei Dynasty (386-534 CE). Afterward, the central axis took shape in the capital cities of the following dynasties: Jankang of the Eastern Jin and the Southern dynasties, Daxing of the Sui Dynasty, and Chang’an of the Tang. The central axis during those periods was based on the main hall facing south and an avenue running through the middle of the palace city, playing an important guiding role in the city’s road network and placing them, along with the city structures, lie symmetrically on both sides of the central axis.

However, commercial areas did not appear on the central axes of capital cities until Dongjing City of the Northern Song Dynasty (960 CE-1127), when a civilian economy began to develop. The urban landscape on the central axis was meticulously planned, functional elements were increased, and the well-ordered landscape was expressed more efficiently. Thus, the central axis became a symbol of state ritual traditions. The central axis of Donging (East Capital) of the Song Dynasty, Zhongdu (Central Capital) of the Jurgen Jin Dynasty, Shangdu (Upper Capital) of the Yuan Dynasty, and Nanjing of the Ming Dynasty all were important examples of the development of Chinese capital’s central axis in a later period.

Compared with the capital’s central axes of the previous dynasties, as above-mentioned, Beijing Central Axis combined the advantages of the central axes in the Yuan Dynasty’s Dadu and the Ming Dynasty’s Nanjing, thus becoming an outstanding example of the development of traditional Chinese capitals’ central axes to maturity. The Beijing Central Axis fully realized the ideal capital city planning paradigm prescribed in the Kao Gong Ji. With its unique planning pattern where several sacrificial buildings are arranged on both sides of the axis in a balanced and symmetrical manner, Beijing Central Axis highlighted the respect for rituals and etiquettes in the construction tradition of Chinese capital cities. In doing so, it became an outstanding model of the traditional Chinese capital central axis that developed to a mature stage. The functions of the Beijing Central Axis were also more complex than other axes. A central avenue connected imperial palaces and gardens, national ceremonial and ritual spaces, as well as urban management facilities. Thus, the Axis displayed the state ritual traditions that continue to this day and the traditional urban management methods. Beijing Central Axis is also the only one of all capital axes in all dynasties in China that has been preserved in its entirety in an architectural form to this day. Its large scale, impressive architectural sequences, and balanced and symmetrical urban landscapes all demonstrate the unique aesthetic value of Chinese traditional capital planning and construction. In addition, the layout and landscape of the Axis have also been respected and carried on in modern city constructions, continue to exert a significant influence on urban development and show the vitality of traditional Chinese planning concepts.

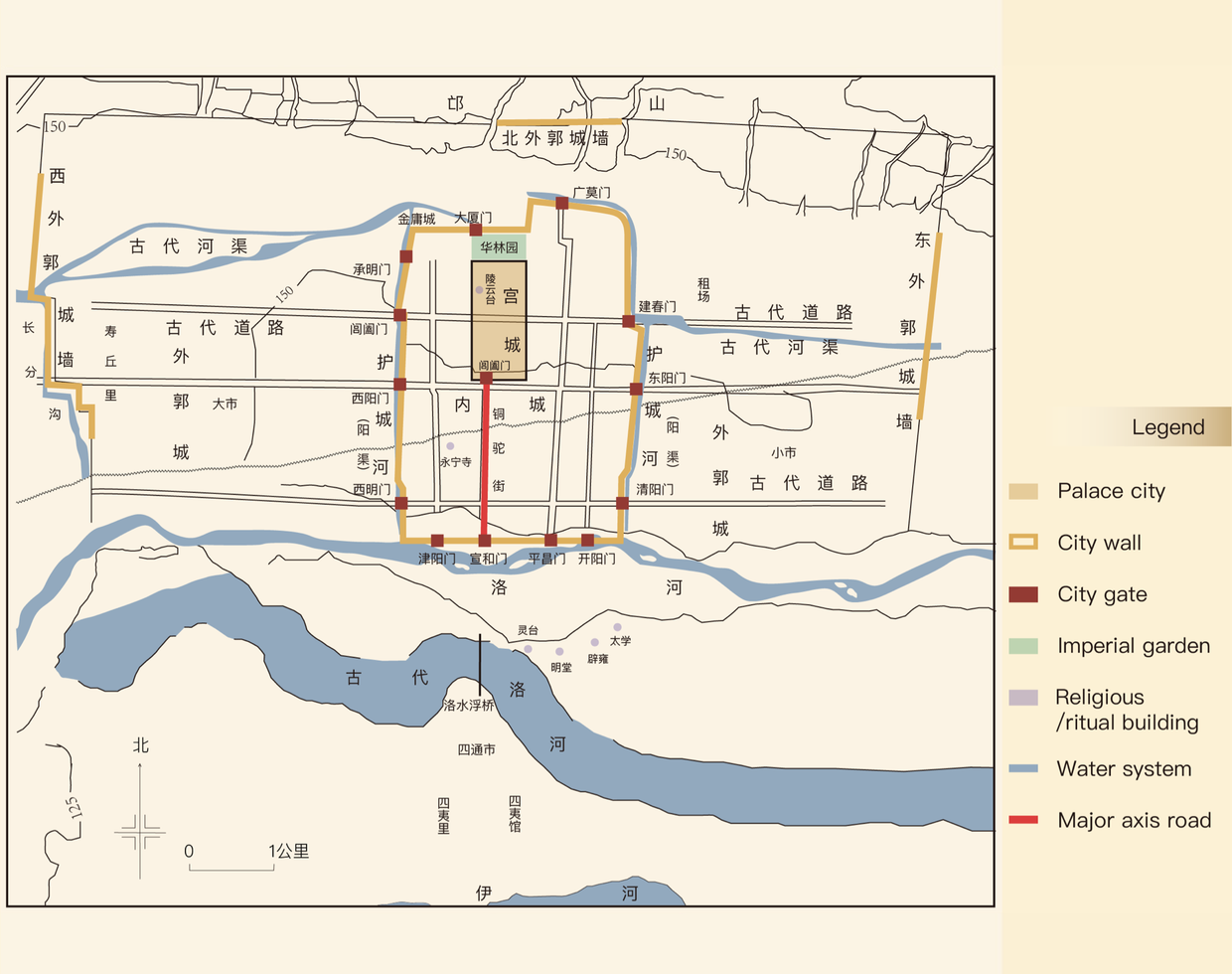

Emperor Xiaowen of the Northern Wei Dynasty moved his capital to Luoyang in 493 CE and built his capital on the basis of Luoyang City during the Wei and Western Jin dynasties. Located 15 kilometers northeast of today’s Luoyang City, the ancient city’s site is an important part of the ancient city remains in the Han and Wei dynasties, which is a key cultural relic under national protection. The ancient city site of Luoyang in the Han and Wei Dynasties is one of ancient China’s most important ruins of capital used by several dynasties: the Eastern Zhou, the Eastern Han, the Cao Wei, the Western Jin, and the Northern Wei. Significant results have been achieved in archaeological and research work focused on the evolution and development of the capital city Luoyang during the Eastern Han, Cao Wei, and Northern Wei dynasties in different historical periods.

The planning of Luoyang City in the Northern Wei Dynasty was significant in constructing ancient Chinese capitals. The urban layout was innovative because it comprised the palace, the inner, and the outer cities. The inner city hosted the palace city, the royal family’s forbidden garden, the offices, the temple of land and grain, the Imperial Ancestral Temple, the arsenal, the national granary, and houses of worship. They were the royal-family facilities in one place encircled by a wall. Outside the wall were the living quarters for the ministers and the commons. A li-fang system was implemented to manage the inner city. Incidentally, under this system, the inner city was divided into wards called li and subdivided into smaller units called fang.

This layout had a lasting impact on constructing the Chinese capital’s central axes in later dynasties. The central axis of the whole city started from the Taiji Hall (the main hall of the palace city), extending south until the Changhemen Gate (the main south gate of the palace city), continuing with Tongtuo Street (the central avenue), and arriving at the Xuanyangmen Gate (the main south gate of the inner city). It ran through the palace city, the imperial garden, and the main city gates, with central government offices distributed on both sides and sacrificial buildings such as Lingtai and Mingtang in the southern suburbs, on the east side of the axis. Streets, alleys, and li and fang were symmetrically laid out on both sides of the central avenue. The existing archaeological site of the central axis of Luoyang City still evokes feelings of magnificence and presents itself as an orderly spatial sequence.

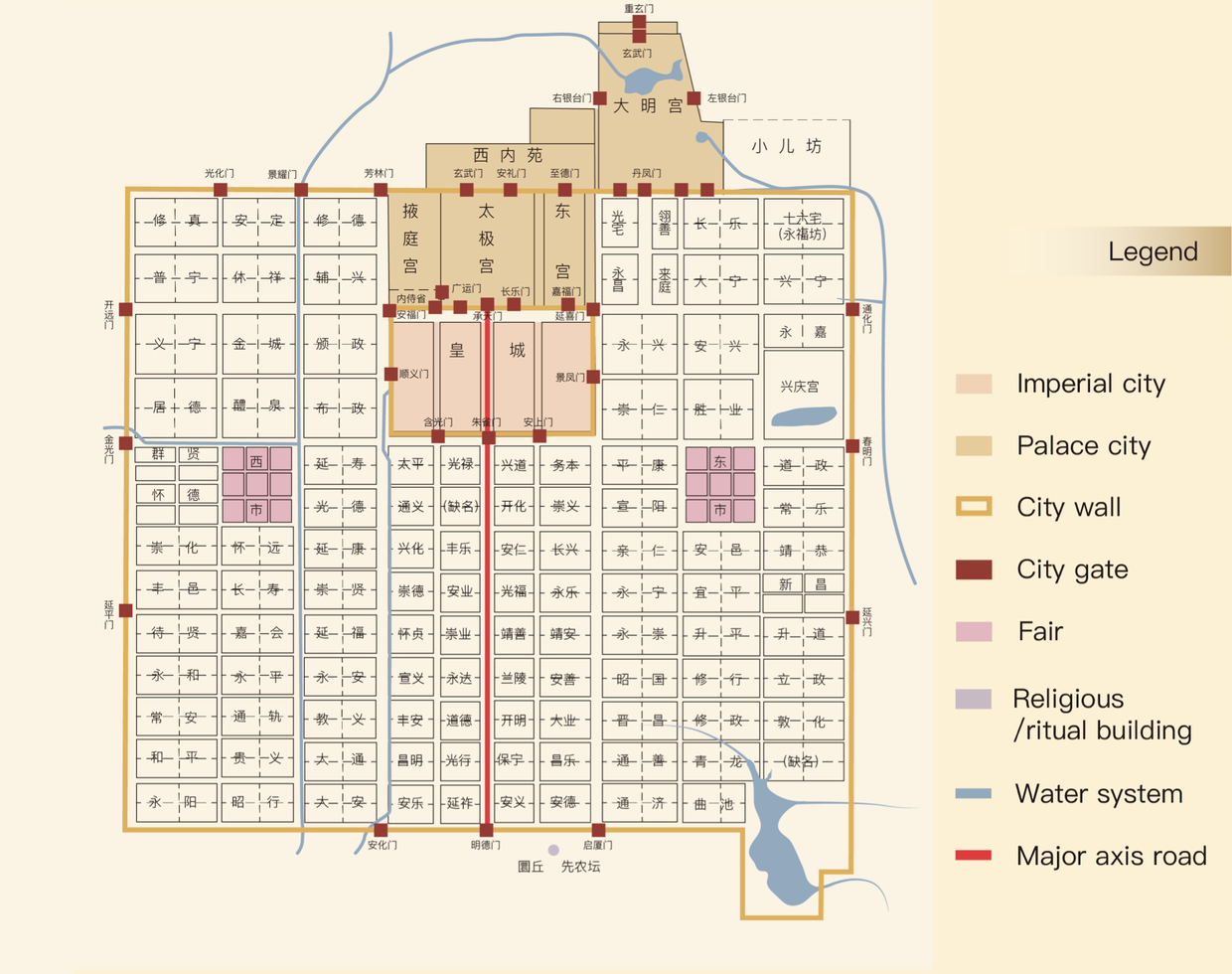

The site of Changan City of the Sui-Tang Period is in present-day Xian, Shaanxi province. The construction of the city began in 582 CE and was the capital of the Sui and Tang dynasties. It was a capital planned and built from scratch and on an unprecedented scale

The plane of Chang’an City in the Tang Dynasty is rectangular, comprising the palace wall, the imperial city, and the outer city, which is 9,721 m (31893.04 ft.) long west-east, 8,651 m (28382.6 ft.) long north-south, and 36.7 km (22.8 mi.) in diameter, covering an area of 83.1 sq km (32 sq. mi.). It was one of the largest cities worldwide. The urban layout and the planning of the central axis in the Tang-era Chang’an City were more meticulous than in previous capitals. The city was rectangular in shape, composed of a palace city, an imperial city, and an outer city. Each of the four outer city walls had three gates. The palace city was located in the center of the northern part of the capital, and to its south was the imperial city where central government offices were concentrated. The imperial garden was located outside the city, to its north. Archeological findings show that the Mingdemen Gate (the main south gate of the outer city) was five carriageways wide, wider than any other city gate. This fully demonstrates the importance of Zhuque Avenue.

Coinciding with the axis of the palace and the imperial cities, Zhuque Avenue (the central avenue) formed the core section of the central axis of the city, connecting the south gate of the palace city and the south gate of the outer city. The Imperial Ancestral Temple and the altar of land and grain were laid out on either side of the central axis, in the southeast and the southwest corners of the imperial city, corresponding to the rules prescribed in the Kao Gong Ji. The framework of the walled city, the distribution of city gates, streets and alleys, lifang, and the east and west markets were laid out along the central axis in a strictly symmetrical manner, demonstrating the important role of the central axis in the overall layout of the city.

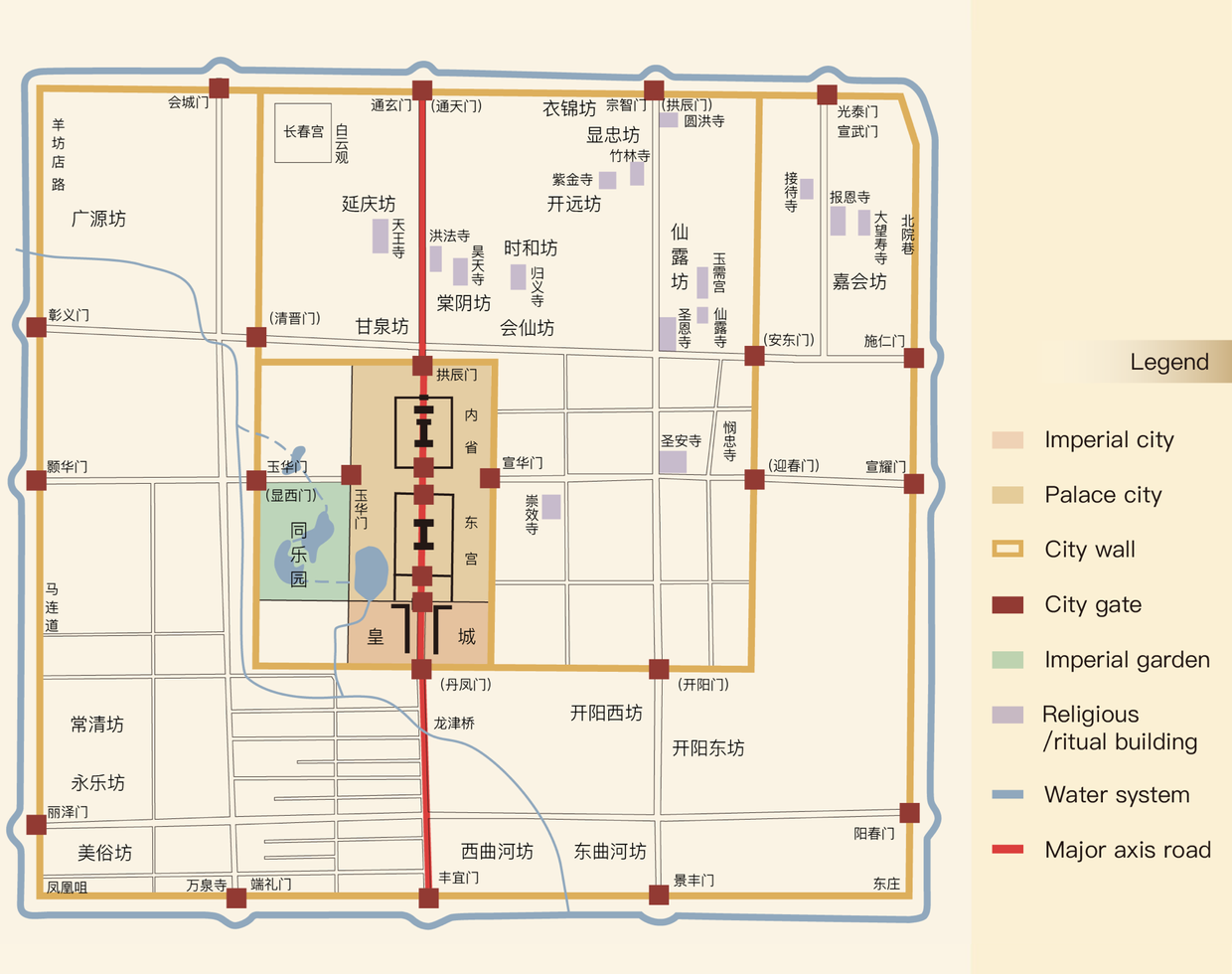

Zhongdu of the Jin (Jurchen) Dynasty was located in the southwest of present-day Beijing. It was built in 1151 and served as the capital until 1214. The whole city was roughly rectangular in shape and had a tri-walled layout, comprising a palace city, an imperial city, and an outer city. The palace city was in the center, slightly to the west. Three gates were opened in the outer city’s east, south, and west walls, and four were opened in the north wall. The palace city lies at the center, crisscrossed by regular roads. The Da Yuan Hunyitong Zhi (Amalgated Geographical Encyclopedia of the Yuan Dynasty) records 62 fangs in the city. Still, the walls encircling the fangs no longer existed, so it was an urban layout where the streets and alleys were open to the outside world. Roads ran through the city.

The avenue between the Tongxuanmen Gate (the main north gate of the outer city) and the Fengyimen Gate (the main south gate of the outer city) and its extension was the north-south central axis of the whole city, on which located the palace city, the imperial city, commercial area, and city gates. The street between the palace city and the main south gate of the imperial city was the imperial avenue, on each side of which there was an imperial corridor, or the so-called thousand-step corridor, where the public could watch national ceremonial activities. They were ceremonial markers and highlighted the importance of the central axis and its ceremonial role. Due to the convenience of water transportation, there was a market area in the north of the city, which, along with the palace city in its south, formed a layout of “the court in the front, and a market in the back,” consistent with the Kao Gong Ji. The Imperial Ancestral Temple was located on the east side of the imperial corridor, conforming to the principle of “an ancestral temple on the left.” What remains on the site of Jin Zhongdu are only part of the city walls and the watergate site. Other important buildings on the central axis have all disappeared.

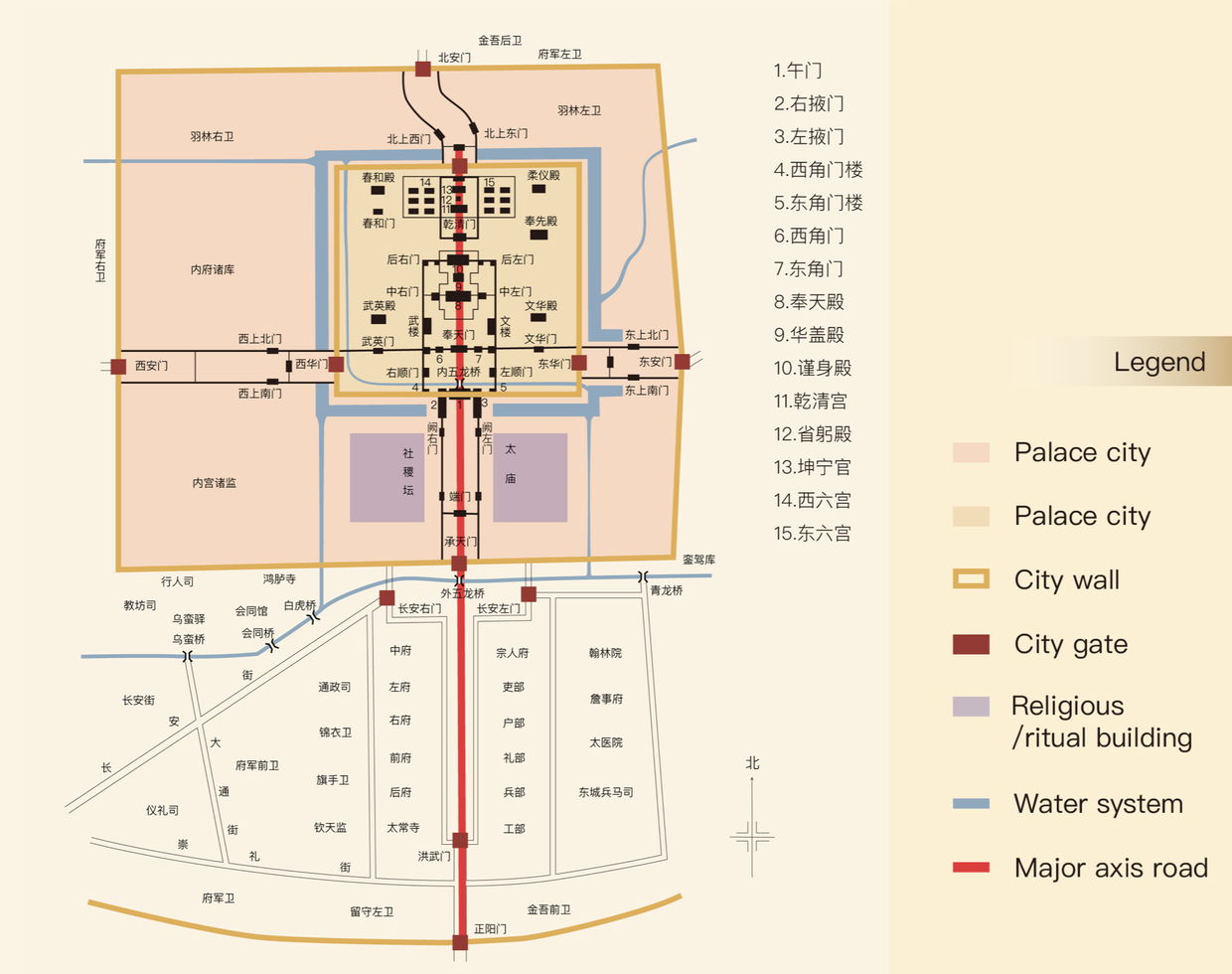

Nanjing City in the Ming Dynasty was built on the basis of Nanjing City of the Six Dynasties Period. The construction of the capital started in 1356 and was finished in 1393.This was the capital of the early Ming Dynasty until the capital was moved to Beijing in 1420.

Nanjing City was composed of a quadruple-layered framework of the walled city: the palace city, the imperial city, the inner city, and the outer city. Located in a hilly area, the inner and the outer cities, where civilians lived, were constructed along surrounding hills, lakes, and rivers, featuring an irregular plan enclosed by defensive city walls. The imperial city was located in the east of the inner city, facing south and in a” “shape. It was where the central government offices and sacrificial buildings were located. The palace city was in the center of the imperial city, slightly to the east, and square in shape. There was a north-south central axis in the palace city and the imperial city.

It took the Fengtian Hall (the main hall of the palace city) as the core, extended southward through the Meridian Gate (the main south gate of the palace city), passed the Up-right Gate, the Chengtianmen Gate, and the Outer Wulong Bridge, and ended at the Hongwumen Gate (the main south gate of the imperial city). The Imperial Ancestral Temple and the Altar of Land and Grain were respectively arranged on the left and right sides of the axis in the imperial city, but the inner city and the outer city were not symmetrical with the axis.